Abstract

To participate or stand aside: Redress processes and historians’ risks and contributions

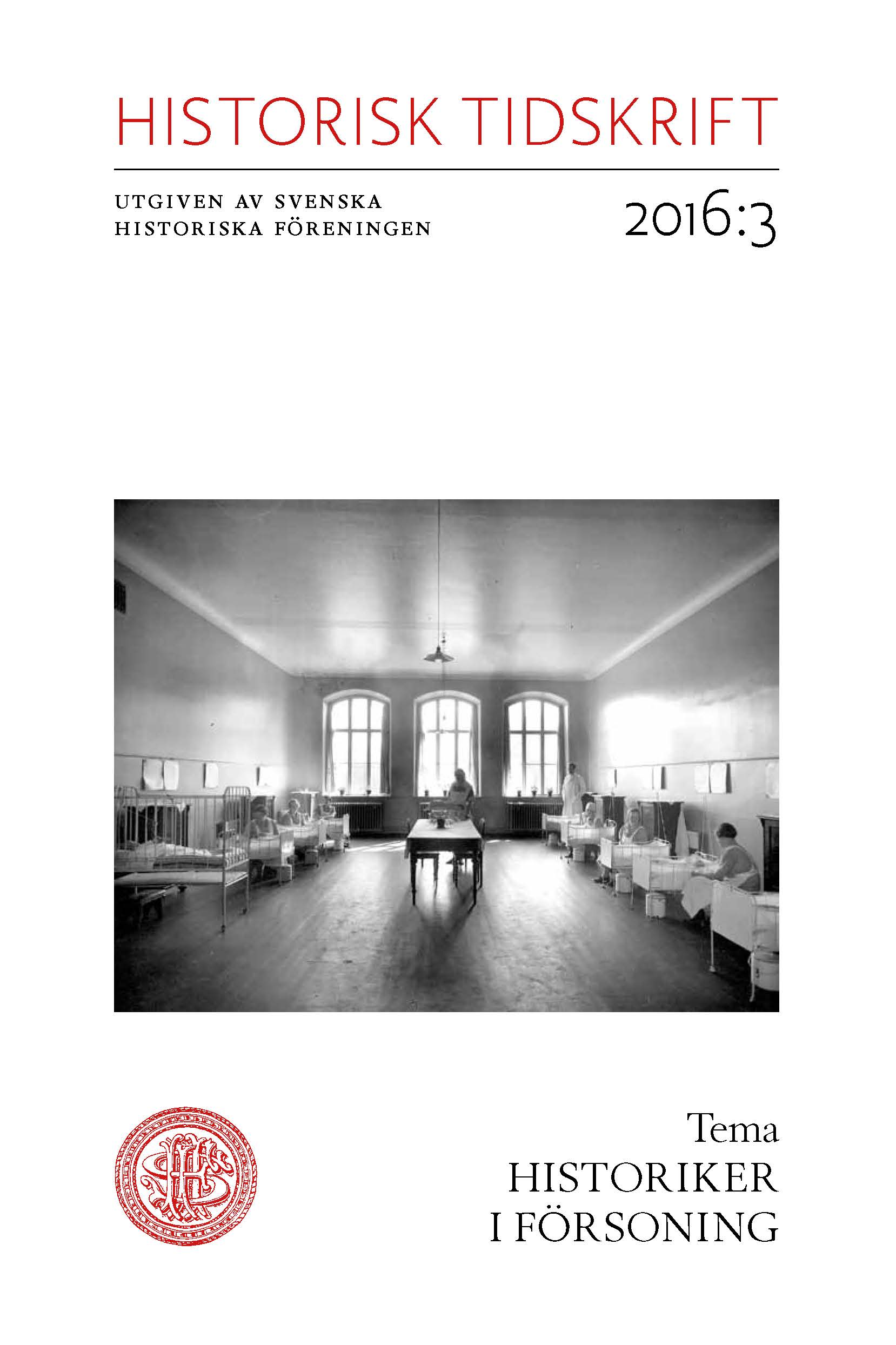

Historical knowledge is crucial for inquiries, truth commissions and redress processes that aim to offer redress to victims of historical child abuse in out-of-home care. The professional competence of historians has much to offer, but taking part in such political processes means that the historian faces certain challenges. This article explores the ethical, emotional, epistemological and methodological risks historians may encounter when involved in redress processes, but also the consequences of historians’ absence from such processes. The authors have contributed with their expertise at various stages of the Swedish redress process and use their own experiences as well as those of other researchers who have been involved in redress processes to discuss the issues at stake.

Inquiries and redress processes addressing historical child abuse within out-of-home care constitute a growing field within reparative justice where historians have as yet figured only in the margins. The authors suggest that historians have an ethical and moral responsibility to contribute to this field. But such contributions mean facing ethical risks because of the blurry distinction in the legal regulations of research ethics, which fails to clearly separate research that require permission from ethical vetting boards from research by official authorities that is exempted from such requirements. In addition, the confrontation with traumatic stories of abuse represents a possible exposure to emotional risks. Historians, who are seldom professionally trained to reflect on their own or their informants’ emotions, need to be attentive to reactions from such exposure and to learn from other academic fields in this respect. The fact that investigators write normative reports for multiple audiences (victims, politicians, academics and the general public) with the objective of both recognizing the victims’ testimonies of abuse as well as offering an account of ’what really happened’, means that the historian have to re-evaluate her/his epistemological stance and maybe also navigate between different methodological approaches such as constructivism and positivism. These challenges are accentuated when individual cases are tested to meet the legal requirements of a financial redress process. Without historical contextual expertise guiding such processes redressing the past can come to rely on anecdotal historical knowledge that distance the past from the present instead of an understanding of how past and present are intersected and how the (non-)existence of measurements to address child abuse have a legacy in our own time.