Abstract

“We must save the children”: Swedish relief committees helping war children abroad in the 1930s and 1940s

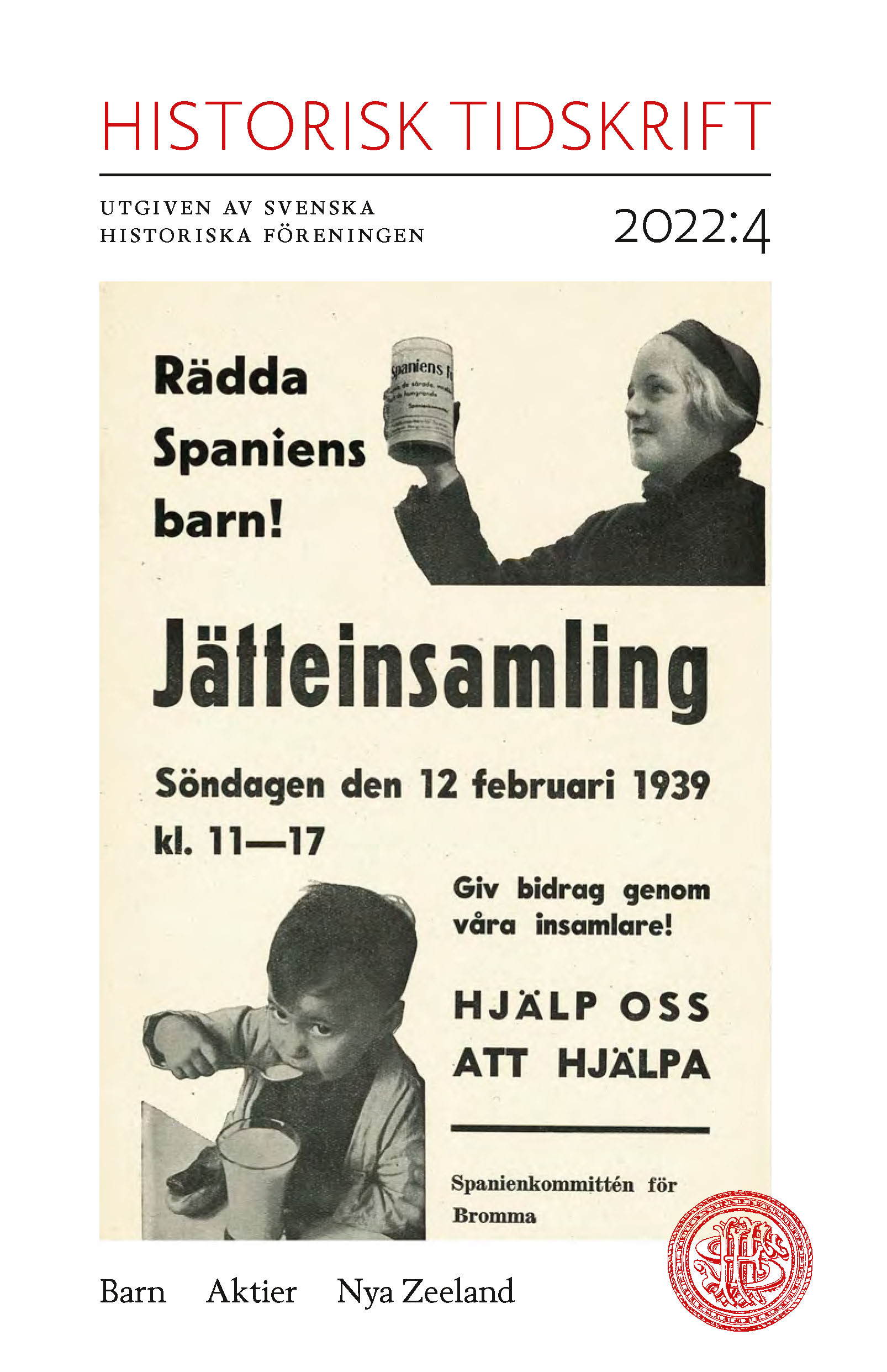

In the first decades of the twentieth century, there were numerous relief actions directed at children exposed to war. Many were carried out by international organisations such as the Red Cross and Save the Children, while in some countries, Sweden among them, temporary voluntary organisations were set up to help children from specific countries or groups. This article examines such initiatives.

Efforts to save children are often understood as non-political, as a commitment to innocent children is perceived as an act of humanity. The present article, however, problematises the nominally neutral character of relief actions by looking at how political and ideological strategies and ambitions were expressed in some of the Swedish relief committees’ work.

Drawing on archival material from four organisations – the Swedish Relief Committee for Spain, the Women’s Committee for the Children of Spain, the Committee for the Children of France, and the Central Relief Committee for the Children of Leningrad – each representing a different political orientation, the article demonstrates their different ways of organising relief actions that ran concurrently and how the committees pursued child relief actions. Some committees were associated with existing organisations, such as trade unions, women’s associations, and political parties; the Committee for the Children of France’s connections, however, were with the export industry and the cultural sphere. All the committees had their own objectives and plans, but in the end their solutions were similar: they all invested in children’s homes. In fact, the four committees operated more than twenty children’s homes abroad.

The committees shared a focus on war children, but each had its own political stance. Some saw political positioning as a way to save children, others felt that political neutrality would serve them better. The article shows that relief actions were not always guided by notions of what was best for children, but by Swedish interests in trade, foreign policy, and mobilisation for domestic policy.