Abstract

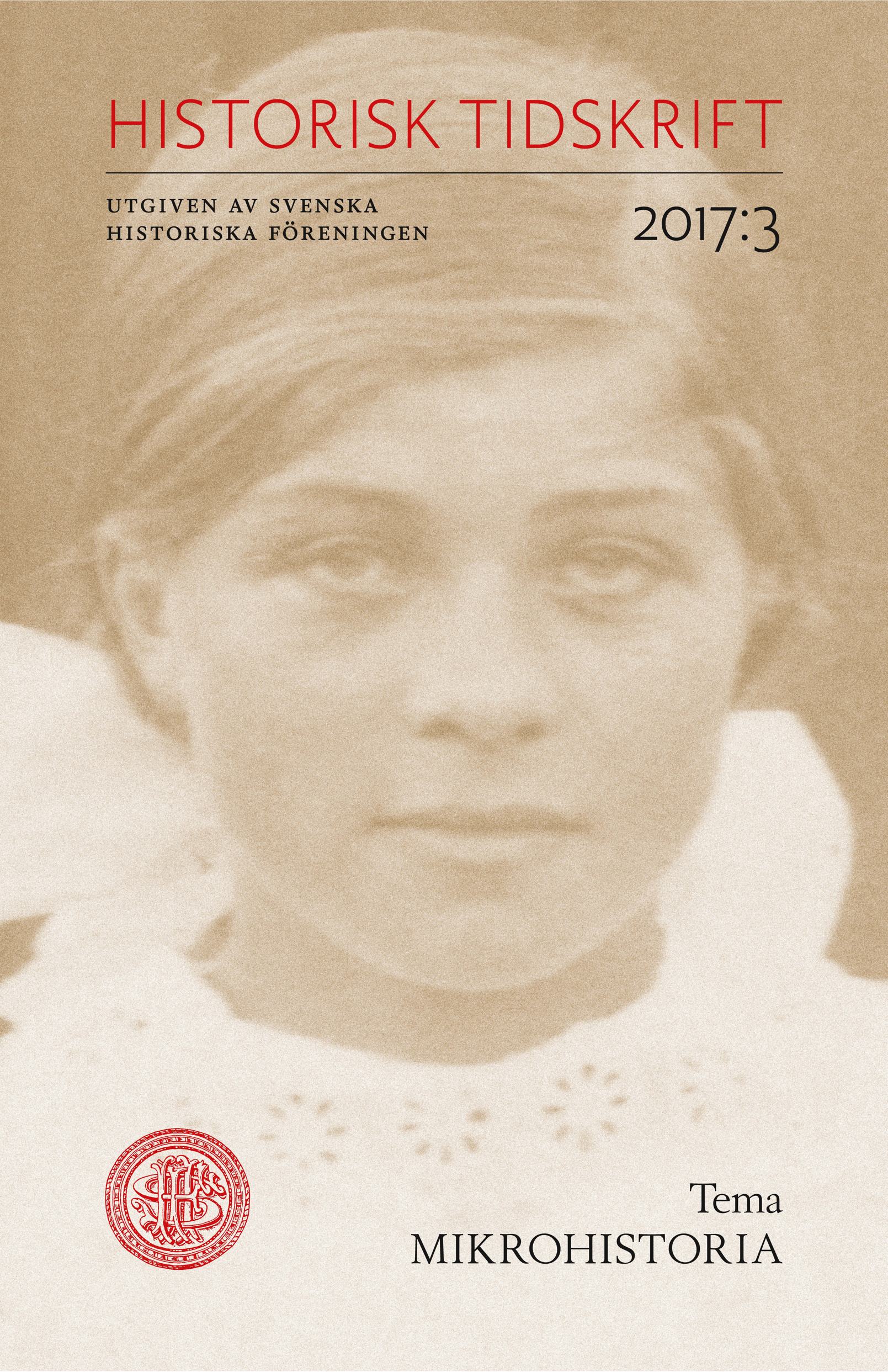

One year with Ester: The social network and emotional life of a junior school teacher through a microhistorical lens

At the dawn of the twentieth century (1901–1902), the nineteen-year-old junior school teacher Ester Vikström kept a diary. Ester worked in a small coastal village in northern Sweden where she was the only teacher. Through a microhistorical approach this study aims to explore the public and private life of Ester by focusing on her social networks and emotional life. The study uses female agency, a life course approach and concepts from the history of emotions to analyze her diary. The main findings show that Ester was very active in the local community and had a broad social network, which included social ties on many different levels in the social hierarchy. Ester had her closest friends among sea captains’ wives, maidservants and a dock workers family, where she met her future husband. However, Ester was also a friend of the most prominent persons in the community, the doctor and the priest. Her everyday life in the village included involvement with numerous associations such as the home sewing association, the temperance movement and a choral society. In the diary Ester shared much of her emotional life by recounting her experiences and thoughts, which were characterized by a wide spectrum of different emotions: Esters physical and psychological status, her thoughts and empathy in the case of accidents or diseases, the interaction with her students etc. One category of emotions and thoughts is distinguished from the others, the relationship to her fiancée and future husband Emil. This can be seen in Ester’s diary because she uses cipher when she writes about her feelings for Emil. The concluding remarks of this study argue that Ester made use of her agency to integrate in the local community. The diary reveals an intriguing and eventful phase in her life course during her pathway to adulthood. Her custom to use cipher when writing about her deepest and most personal emotions can be viewed as a way to write about something that was not really accepted by the predominant “emotional regime” in the village.